Today there is an unprecedented thirst for the innermost secrets of Christianity. The quest for these lost teachings drives the plots of best-sellers like The Da Vinci Code and Holy Blood, Holy Grail; it is discussed in major newsmagazines; and it is the subject of intense speculation and debate among believers and nonbelievers alike. What are these secrets? What difference might they make to our lives today?

Sometimes the hidden truths of Christianity are described in terms of suppressed facts about Jesus’s life. One of the most popular at present is the idea that he was married to Mary Magdalene and even had children with her. Some say Joseph of Arimathea brought these children to Britain after Christ’s death.

There are some intriguing hints of these ideas in the written texts. In one apocryphal Gospel, for example, Jesus is described as kissing Mary Magdalene frequently on the mouth. The other disciples become jealous and start to grumble, “Why don’t you love us as you love her?” Jesus turns to them and says, “Why don’t I love you as I love her?” – the answer, presumably, being obvious enough.

But there is, of course, no real proof that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene or that they had children. And even if it could be proven, what difference would it really make? What would it matter even if their descendants had survived to this day? The bloodline would have been so diluted over the course of two thousand years that the connection would be extremely tenuous in any event.

Consequently, while speculations about Christ’s private life may fascinate us as we are fascinated by gossip about celebrities, in the end it can be little more than an entertainment. If these are the ultimate secrets of Christianity, they are rather disappointing.

Sometimes, however, these hidden truths are portrayed in another light. In a recent article on Jesus and the lost Gospels, the American newsmagazine Time observed that, according to Gnostic teachings, Christ’s task was to transmit a “special wisdom” that confers spiritual liberation. Unfortunately, as the article goes on to say, this wisdom “is alluded to but not spelled out” in Gnostic texts.

While the Time article is correct in saying that this wisdom is not spelled out in the Gnostic texts, the knowledge has by no means been lost. It has been preserved in the esoteric tradition of Christianity, which has survived in an unbroken line from Christ’s day to the present. It can be found in obscure texts, oral teachings – even in the canonical Gospels when they are read at a level beyond the merely literal.

These truths have, it is true, become obscured and concealed, for a number of reasons, some good, some not so good. But before I can explain why they came to be hidden for so long, let me spell out briefly what, I believe, the essence of this wisdom is. It’s not particularly difficult to understand, although it will be somewhat easier to grasp if you have some meditative experience.

Discovering the True “I”

The best way to introduce it is by means of a simple exercise. Sit comfortably, in a relaxed but alert position. Have your back as straight as possible; you can prop yourself up with pillows against the back of a chair if you like. Let your attention settle down, and, to the best of your ability, allow the ordinary preoccupations of your day to subside.

Look around the room you are sitting in. It may or may not be familiar; that does not matter. Only be sure to cultivate a sense of the presence of yourself as you sit in your chair. This is where you are; around you, outside you, is the visible and sensible world.

Now close your eyes and bring your attention to your body. Be aware of your sensations – the breath, perhaps, or the beating of the heart, or the feelings in your back as it presses against the chair. If you pay attention, you can catch a glimpse of two things: an experience, a muscle sensation, say, and an “I” that is experiencing it.

Go deeper still, to the river of thoughts, images, and emotions that are probably coursing in front of your mind. You may try to stop the flow of this stream of consciousness, as it has sometimes been called. Probably you will fail. The thoughts and images, memories, ideas, speculations, plans will most likely continue whether you want them to or not.

In this realm also you can observe two things: an “I” that is experiencing and something that is experienced. As you continue, even your most intimate feelings and desires will pass before you like images on a screen. If you can remain both relaxed and alert (admittedly a difficult balance), you may have a sense of something very quiet and small in you. It seems to have no power, no volition of its own, yet it is that in you which is constantly awake and experiences all that passes for your life. In the strictest sense, you cannot even observe it, for it is actually that which observes. If you look for it, you find that it continually recedes further and further, for there is no limit to this “I” that experiences. You can follow this thread of consciousness back for as long as you like, but you may find this exercise to be of value even if you can only do it for a few seconds.

What Is the Kingdom of Heaven?

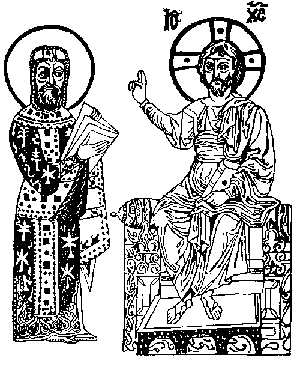

If you read the New Testament carefully, you will notice that the synoptic Gospels – Matthew, Mark, and Luke – often refer to a mysterious entity known as “the kingdom of heaven” or “the kingdom of God.” Christ describes it in parables, likening it to a mustard seed, to leaven, to a treasure hidden in a field. In John, on the other hand – long known to be the most “esoteric” of the Gospels – Christ does not speak in parables. Instead he describes the kingdom of heaven by using “I am” statements: “I am the door”; “I am the true vine”; “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” You will also remember from Exodus, when Moses encounters the Lord in the burning bush, that the highest name of God is “I am that I am.”

These texts point to the same truth that you may have experienced while doing the exercise above. The kingdom of heaven is that in you which says “I.” This is not the ordinary ego, with its bundles of agendas, desires, and loathings. In its purest, most naked form, this true “I” is consciousness – a consciousness that we share with the entire universe, animate and inanimate. So when Christ says, “I am the way, the truth, and the life,” esoterically speaking, he is saying, “‘I am’ is the way, the truth, and the life.” “I am” is the door through which we must proceed to enter the kingdom – that is, to recognise and understand this truth experientially.

The inner Christian tradition has a name for this experiential recognition: it is called gnosis, or “knowledge” in the true sense. Although gnosis is often regarded as something rather mysterious, as you can see, the fundamental insight behind it is comparatively simple. Understanding it doesn’t require vast amounts of learning or scholarship. But there are a number of things that interfere with this recognition, which suggests why this truth is so frequently lost and so frequently needs to be discovered anew.

Remember Christ’s parable about the kingdom of heaven being “like unto a treasure hid in a field” (Matt. 13:44). In terms of the exercise above, the consciousness, the “I” that is fundamentally you, is buried in a “field.” This is the field of your own experience – your thoughts, emotions, feelings, your pleasures and pains. You become identified with this experience, forgetting that there is something beyond it – the experiencer, the “I” that is eternal and undying and immune to all destruction and decay. But if you remember the truth of what you are – or rather of what this “I” is – you unearth the treasure from the field. And as the parable goes on to say, that is worth the price of everything else put together.

Death and Resurrection

It is written that “God loved the world.” Like God, consciousness, this “I” that stands at the back of each of us, witnessing and experiencing our lives through us, loves the world it has made. It loves this world so much, in fact, that it rushes forth to unite with it, becoming lost in the process. In the Gnostic Gospels, this is likened to a pearl that is lost at the bottom of the sea. But the most famous metaphor for this process forms the central drama of Christianity: death and resurrection.

When the “I” is submerged in and identified with its own experience, this is, esoterically, known as death. In Genesis God tells Adam that if he eats of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, he will surely die. This doesn’t refer to physical death, but to the “death” of consciousness in the darkness of its own experience. The passion, death, and resurrection of Christ portray this process allegorically. The God-man is crucified. He suffers all sorts of pain and indignities, and finally perishes in an ignominious fashion. But in the end it does not matter, because he rises again in a glorified form.

This is Christ’s story. It is our story as well. We are crucified on a cross known as time and space. We pass through life, which often seems to offer no end of sorrow, pain, and humiliation. And in the end we die. But in fact nothing that is real or true about us dies. The true “I,” the consciousness that is the only real and eternal part of us, goes on to live in a new and different form.

This is a universal truth, so it has always been known. The ancients before Christ expressed it in the form of mystery religions. While we don’t know exactly what went on in the Eleusinian or Dionysian mysteries, we do know that in essence they were about death and resurrection. Here the great mystery of the death and rebirth of consciousness was expressed in ritual form. As the great esoteric visionary Rudolf Steiner pointed out, with the coming of Christ, what had been conducted secretly, in the mystery religions, was now carried out publicly and in full view. And the “good news” of this truth was proclaimed to all nations.

The Truth Hidden

Ironically, as this truth was proclaimed far and wide, its essential meaning came to be submerged. Rites like the mass were instituted to commemorate the passion of Christ, but it was forgotten that Christ’s own passion was to remind us of our own situation.

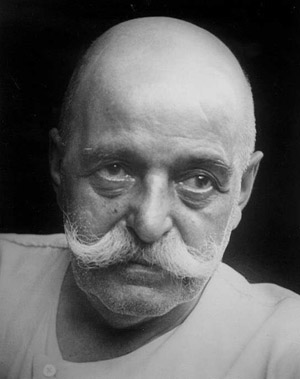

As the spiritual master G.I. Gurdjieff pointed out, “The Christian church is a school concerning which people have forgotten it is a school. Imagine a school where the teachers gives lectures and perform explanatory demonstrations without knowing that these are lectures and demonstrations; and where the pupils or simply the people who come to the school take these lectures and demonstrations for ceremonies, or rites, or ‘sacraments,’ i.e., magic. This would approximate to the Christian church of our times.”

But why did this happen? How did the central message of Christianity come to be so thoroughly occluded for so long? This happened for several reasons. In the first place, the insight toward which this article has been pointing is not always that easy to grasp. It can be difficult for consciousness to look back upon itself, especially since, as I’ve suggested, this true “I” can never be seen, because it is always that which sees. As St. Francis of Assisi put it, “What you are looking for is what is looking.”

Moreover, now as in the past, people by and large tend to want an external religion, an external God who controls their destinies and can damn them or, being duly appeased, save them from damnation. This is not really an accurate picture of the human condition, but people tend to fall back on it because it’s easy to grasp. It was even more so in the formative times of Christianity, when religions of all sorts – at least in the West – were preoccupied with coaxing the gods through sacrifice. When Christianity came onto the scene, it was almost immediately recast in the same terms. Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection were seen, not as a reminder of the deepest truth about ourselves, but as an appeasement of a petulant deity. Two thousand years later, it’s clear that this model does not make any sense, but people haven’t managed to find anything plausible in its stead. That’s why it’s time to reintroduce and restate these central truths.

Another issue has to do with the social role of religion. Religion has two functions in society, which don’t always jibe well with each other.

In the first place, it’s meant to help individuals make contact with the higher dimensions of their own being. In the second place, it serves as a guarantor of the social order. Since societies can’t afford to have policemen watching over everyone’s shoulder at every moment to make sure they behave, they have found it helpful to install an internalised policeman into the human psyche. This policeman usually takes the form of an all-seeing God who watches our every move and keeps an elaborate tally of our good and bad deeds, for which we will be recompensed accordingly in the afterlife.

Unfortunately, the notion of an external God who rewards and punishes, while it is a convenient way to oil the wheels of the social order, tends to interfere with personal experience of the divine. People are led to feel guilty and unworthy. Like Cain after murdering Abel, they hide from the voice of God.

Archons and Conspiracies

These reflections have led some people to view the social and political order as a massive conspiracy whereby a privileged few manipulate the psyches of the masses in order to retain their position at the top. Although it’s certainly true that in many ways the social order is run by and for the benefit of comparatively few individuals, it has never seemed plausible to me that they manipulate these social mechanisms in the way they’re sometimes portrayed. Human beings, in their unenlightened condition, are simply social mammals – and mammalian societies have pecking orders. While those at the top may benefit from their position, it doesn’t follow that they’ve created the system or even understand it particularly well. They’re simply fighting to stay on top. This is no less true of the pope or the president of the United States than it is of an alpha male in a pack of wolves.

Speaking of conspiracies, I might point out that certain esoteric Christian texts, notably those categorised as Gnostic, refer to a corrupt and wicked cosmic order. This evil system goes far beyond mere political and economic conspiracies. As the Epistle to the Ephesians puts it, “we struggle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” (Eph. 6:12). The Gnostic texts speak of entities known as archons or “rulers.” These entities, which have peculiar names like “Oblivion” and “Deficiency,” are sometimes portrayed as inimical angels that bar the way to the paradise of union with God. Is there any truth to this concept?

As sometimes happens, the truth may be both more and less terrifying than it seems at first glance. Certainly it would be disheartening to believe that evil archangels, with powers far surpassing those of mere humans, lurk over us to keep us incarcerated in our little pen in the cosmic order. It may be more dismaying still to realise these archons exist, not in the spiritual stratosphere, but within the very structure of our minds and brains.

The archons of Gnostic mythology resemble what the philosopher Immanuel Kant called the “categories.” These are basic modalities – such as space, time, quantity, and causality – by which the human mind structures its own experience. These categories shape our experience of the world, because this is how our brains work. At the same time, the world isn’t really this way; it’s just the way we experience it. From this insight, Kant concluded that the world as it is in itself is unknowable: we will always be limited by the construction of our own minds.

Esoteric traditions of both East and West would agree with Kant that our customary ways of seeing are limited and constrained. But they don’t agree that we are stuck here. By attaining gnosis, also known as enlightenment, we can free ourselves from the world our brains have made and see a higher reality.

Some accomplish this realisation spontaneously: it comes unbidden and unsought, a gift from heaven. These events are real enough; you only need open a book like William James’s Varieties of Religious Experienceto come across many examples of them. But this kind of instantaneous realisation doesn’t occur for most of us. We require systems of spiritual training and practice to liberate ourselves from that subtle and invidious master known as the human mind. Meditation is one of the most universal methods for achieving this end, because in most of its forms meditation stills the consciousness and helps it to cut loose, even if only for a few moments, from the constraints of ordinary experience.

In this way, we can begin to make that most difficult journey, which leads us away from the world we know to the world as we can know it, and on which faith is only the first step toward knowledge.

© Copyright 2004 by New Dawn Magazine. This article first appeared in New Dawn No. 84 (May-June 2004). For further information visit www.newdawnmagazine.com