Of all the earliest followers of Christ, none has sparked the level of interest generated by one particular woman – the biblical figure known as Mary Magdalene. Revered as a saint, maligned as a prostitute, imagined as the literal bride of Christ, Mary of Magdala stands apart as an enigmatic individual about whom little is actually known, despite centuries of scholarly scrutiny and wild conjecture.

All that most Western Christians know about her is presented in the New Testament Gospels, and even that information is disputed. But there is some general agreement: She was a faithful disciple of Jesus Christ whom he had delivered from “evil spirits and infirmities.” Along with several other women, she ministered to Christ and witnessed his death on the Cross. She was there when his body was placed in the tomb, when the stone was rolled away to reveal an empty chamber, when an angel announced that Christ had risen from the dead – and when he made His first post-Resurrection appearance to the living. She brought the news of his Resurrection to the other disciples.

For 1,500 years, Mary Magdalene was portrayed, in art and theology, as a prostitute whose life was transformed by Jesus’ forgiveness. This notion, based on Luke 7:38, was the result of an erroneous sermon preached in 591 by Pope Gregory the Great. Jean-Yves Leloup, in his commentary onThe Gospel of Mary, states:

Mary’s identity as a prostitute stems from Homily 33 of Pope Gregory I, delivered in the year 591… Only in 1969 did the Catholic Church officially repeal Gregory’s labeling of Mary Magdalene as a whore, thereby admitting their error – though the image of Magdalene as the penitent whore has remained in the public teachings of all Christian denominations. Like a small erratum buried in the back pages of a newspaper, the Church’s correction goes unnoticed, while the initial and incorrect article continues to influence readers.1

The stain of immorality attached to the figure of Mary Magdalene averted attention away from the significant role she plays in the unfolding of Christ’s teachings. The importance of Mary is especially apparent in Gnostic texts – some among the earliest accounts of Jesus’ ministry – which have been largely suppressed and ignored by Church authorities.

The Gnostic picture of Mary departs – in some ways, dramatically – from the historical and biblical image of perhaps the most significant female follower of Jesus.

The second-century Gospel of Mary was found in the late 19th century by archaeologists but remained largely ignored and untranslated for 50 years. It is the only account named for a woman and offers a different view of Christianity – one that describes an “interior spirituality,” says Karen L. King, author of The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle.

In the Mary Magdalene account, “salvation is not something that comes from an external saviour,” says King. “One has to seek salvation within.” Thus, the Magdalene gospel depicts Jesus as a teacher rather than as a saviour who dies to atone for humanity’s sins.

In her introduction in The Complete Gospels, Karen King says:

…the Gospel of Mary communicates a vision that the world is passing away, not toward a new creation or a new world order, but toward the dissolution of an illusory chaos of suffering, death, and illegitimate domination. The Saviour has come so that each soul might discover its own true spiritual nature, its ‘root’ in the Good, and return to the place of eternal rest beyond the constraints of time, matter, and false morality.

Another Gnostic text – The Gospel of Thomas – reveals that women were disciples of Christ. However the New Testament only includes gospels written by men and distinguishes between the women of Christ’s life, and the ‘disciples’ – who are all male.

You find in the [Gnostic] Gospel of Thomas that six disciples are named: Matthew and Thomas, James and Peter, Mary Magdalene and Salome,” says Prof. Elaine Pagels, professor of religion at Princeton University, and author ofThe Gnostic Gospels and Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas.

Here, explicitly, Mary Magdalene is Jesus’ disciple. In the Gospel of Thomas and also the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, she is seen as an evangelist and a teacher, somebody who is gifted with revelations and teachings from Jesus which are very powerful and which enable her to be a spiritual inspiration to others.

The Gnostics honoured equally the feminine and masculine aspects of nature, and Prof. Pagels argues Christian Gnostic women enjoyed a far greater degree of social and ecclesiastical equality than their orthodox sisters.

For Jean Yves-Leloup, the founder of the Institute of Other Civilisation Studies and the International College of Therapists, Mary Magdalene is the intimate friend of Jesus and the initiate who transmits his most subtle teachings.

His translation of The Gospel of Mary is presented in his book The Gospel of Mary Magdalene along with a commentary on the text which was discovered in 1896, nearly 50 years before the Gnostic Gospels at Nag Hammadi were found.

In his book, Leloup states: “It is Miriam of Magdala who serves the disciples as a midwife, not of body or soul, but of the eternal Son whose Presence seeks to reveal itself in the very heart of that which trembles most within them.”

The Gospel of Mary

Peace be with you. Receive my peace to yourselves. Beware that no one lead you astray, saying, ‘Lo here!’ or ‘Lo there!’ for the Son of Man is within you. Follow after Him! Those who seek Him will find Him. Go then and preach the gospel of the kingdom. Do not lay down any rules beyond what I appointed for you, and do not give a law like the lawgiver lest you be constrained by it.

– Jesus as quoted in The Gospel of Mary

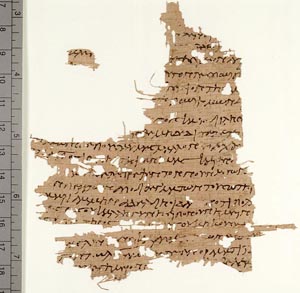

The Gospel of Mary comprises the first part of the so-called Berlin Papyrus. This manuscript was acquired in Cairo by C. Reinhardt, and has been preserved since 1896 in the Egyptology section of the national museum of Berlin.

This copy of The Gospel of Mary, reports Jean Yves-Leloup, “was made in the early fifth century… The scribe wrote down twenty-one, twenty-two, or twenty-three lines per page, with each line containing an average of twenty-two or twenty-three letters. Several leaves are missing from the document: pages 1 to 6, and 11 to 14. This renders its interpretation particularly difficult.

As to the dating of the original text upon which the copy was based, it is interesting to note that there exists a Greek fragment – the Rylands papyrus 463 – whose identity as the precursor of the Coptic text has been confirmed by Professor Carl Schmidt. This fragment comes from Oxyrhynchus and dates from the beginning of the third century. The first edition of the Gospel of Mary, however, would likely be older than this, that is, from sometime during the second century. W. C. Till places it around the year 150. Therefore it would seem, like the canonical gospels, to be one of the founding or primitive texts of Christianity.

The Gospel of Mary can easily be divided into two parts. The first section (7,1-9,24) describes the dialogue between the risen Christ and the disciples. He answers their questions concerning matter and sin.

“Christ teaches that sin is not a problem of moral ignorance so much as a manifestation of imbalance of the soul,” says James Robinson, Professor Emeritus of Religion at Claremont Graduate University.2 “Christ then encourages the disciples to spread his teachings and warns them against those who teach of spirituality as an external concept rather than as an internal, Gnostic experience,” says Robinson.

After he departs, however, the disciples are grieved and in considerable doubt and consternation. Mary Magdalene comforts them and turns their hearts toward the Good and a consideration of Christ’s words.

The second section of the text (10,1-23; 15,1-19,2) contains a description by Mary of special revelation given to her by Christ. At Peter’s request, she tells the disciples about things that were hidden from them. The basis for her knowledge is a vision of the Lord and a private dialogue with Him. Unfortunately four pages of the text are missing here so only the beginning and end of Mary’s revelation are available.

Commenting on the text, Karen King writes: “The first question Mary asks Christ is how one sees a vision. The Christ replies that the soul sees through the mind which is between the soul and the spirit. At this point the text breaks off. When the text resumes at 15,1, Mary is in the midst of describing the Christ’s revelation concerning the rise of the soul past the four powers. The four powers are most probably to be identified as essential expressions of the four material elements. The enlightened soul, now free of their bonds, rises past the four powers, overpowering them with her gnosis, and attains eternal, silent rest.”

This fragment of the gospel describes Mary’s vision of the soul’s ascent beyond the “powers” including the powers of fear. For the Gnostics, these “powers” are the Archons which act as cosmic prison wardens, attempting to prevent souls ascending to the True God. “It (the soul) has to overcome the powers of fear and the powers that threaten it as it proceeds into a life beyond death,” Prof. Elaine Pagels explains.

After Mary finishes recounting her vision to the disciples, Andrew and then Peter challenge her on two grounds. First of all, Andrew says, these teachings are strange. Secondly, Peter questions, would Christ really have told such things to a woman and kept them from the male disciples. Levi admonishes Peter for contending with the woman as against their adversaries and acknowledges that Christ loved her more than the other disciples. He entreats them to be ashamed, to put on the “perfect man”, and to go forth and preach as Christ had instructed them to do. They immediately go forth to preach and the text ends.

This confrontation between Mary and Peter is well documented in a number of Gnostic scriptures. Mary exposes the small mindedness and superficiality of Peter and Andrew who find it difficult to comprehend, let alone accept, the deeper spiritual understanding Mary acquired through her personal experience and closer relationship with Christ.

James Robinson observes: “Indeed Peter and Andrew seem to prefer the very thing against which Christ warned them – a religion based on arbitrary ideas (in this case represented by Peter’s male chauvinism and Andrew’s ignorance). And yet many of their ideas have shaped modern Christianity while, paradoxically, Mary Magdelene’s spirituality, which here seems more consistent with the teachings of Christ, is unheard of today.”

Other Gnostic Texts

Mary Magdalene plays a prominent role in Gnostic traditions presented in other Gnostic works such as Pistis Sophia, The Dialogue of the Saviourand The Gospel of Philip, where she is extolled as a chief disciple of Christ, a visionary and mediator of Gnostic revelations.

In these texts she is praised as “the woman who knew the All” (The Dialogue of the Saviour), and “the inheritor of light” (Pistis Sophia), associated with the divine Wisdom.

The Gospel of Philip recognises her as the koinonos (companion or consort) of Christ whom he loved more than all the other disciples, and the spiritual union between Christ and Mary Magdalene is described in slightly erotic terms. According to Yuri Stoyanov in his book The Other God, “as a terrestrial companion of the Saviour in The Gospel of Philip, she could indeed have been seen as a ‘counterpart of the celestial Sophia’.”

Mary Magdelene as the “consort” of Christ has led some writers to deduce a very different sort of relationship between Mary Magdalene and Jesus, even one in which the two were married and had children.

The Gnostic view of their relationship indicates one in which Mary becomes spiritually pregnant and perfect from her sacred partnership with Christ. When it is reported in The Gospel of Philip Jesus “used to kiss her [Mary Magdalene] often on her mouth”, the Gnostics say a kiss on the mouth was a symbol for passing “knowledge” (gnosis), so the jealousy of the disciples was not to do with the fact Jesus “loved” Mary Magdalene, but the fact he is giving her far more knowledge than them.

One of the most intriguing of discoveries of the late nineteenth century was the Pistis Sophia (“Faith Wisdom” or “Faith of Wisdom”), an allegorical account of the Gnostic world-system. This text claims to report the interactions of Jesus Christ and the disciples after His Resurrection, but it differs radically from the canonical texts in its account of the spiritual powers ruling the universe, its belief in reincarnation, and its extensive use of magical formulae and invocations.

The text describes Jesus as a mystic teacher, whose main interactions are with powerful female disciples like Mary Magdalene. Much of it concerns the stages by which Jesus liberates the supernatural (and female) figure of Sophia, heavenly Wisdom, from her bondage in error and the material world, and she is progressively restored to her previous divine status in the heavens.

To the ancients, the feminine principle Sophia was the veiled holy spirit of wisdom, pregnant with knowledge and inviting us to drink deeply from Her Cup. In Gnostic cosmology, Sophia is trapped in the material world and is liberated after mystical union with Christ. It’s also interesting to note the functions of the Holy Spirit are associated in biblical texts with women: consolation, inspiration, emotional warmth, and birth of the spirit.

Characteristic of these Gnostic gospels, the events described occur symbolically and psychologically, in sharp contrast to the literal interpretation of gospel accounts of historical Christianity.

Gnosticism and the Role of Women

By all apostolic accounts, Yeshua of Nazareth himself was certainly not a founder of any “ism,” nor of any institution. He was the Annunciator, the Witness, and some would go so far as to say the Incarnation of the possible reign of the Spirit in the heart of this space-time, the manifestation of the Infinite in the very heart of our finitude, the voice of the Other within the speech of human-ness.

– Jean-Yves LeLoup3

In Gnosticism: New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing, a modern day Gnostic bishop Stephan Hoeller states that Gnostic Christians hold a “conviction that direct, personal and absolute knowledge of the authentic truths of existence is accessible to human beings, and, moreover, that the attainment of such knowledge must always constitute the supreme achievement of human life.”

As Elaine Pagels says in her book The Gnostic Gospels, this emphasis on spiritual experience did not bode well for the Gnostics. If salvation is directly available to the individual, why does one need an organised church to act as a dogmatic mediator between the individual and God? In Gnostic rituals, the participants would take turns officiating, and in their acceptance of the equality of women they seem remarkably modern.

The confrontation between Peter and Mary Magdalene in The Gospel of Mary is representative of a conflict within Christianity that persists to this day. The story symbolises the confrontation between the traditional Apostolic-Pauline branch of Christianity and the Gnostics. It is also the conflict between the esoteric (the inner or mystical teachings) and the exoteric (the open or exterior teachings) dimensions of religion.

In the early days of Christianity the hierarchical organised church saw the Gnostic mystics, with their subversive openness of spirit and anti-authority stance, as a dangerous threat to its growing power. Unlike the Roman church, in Gnostic groups women were openly functioning as priests and teachers and enjoyed acceptance.

In the 2nd century CE, the Church Father Tertullian particularly objected to “those women amongst the heretics” who held positions of authority. He angrily attacked “that viper” – a woman who was the spiritual teacher of a Gnostic group in northern Africa.

He was outraged, writing: “These heretical women – how audacious they are! They have no modesty. They are bold enough to teach, and engage in discussion; they exorcise; they cure the sick, and it may be they even baptise!… They also share the kiss of peace with all who come.”

Although his views were in line with Jewish tradition from which Jesus had come, it is worth remembering Jesus himself had violated these conventions by openly communicating with women and including them amongst his most intimate followers.

By the 4th century CE the established Christian church was persecuting all Gnostics they could find, and killing them in the thousands. However, the Gnostic stream was not eliminated and remains underground to this very day.

The supreme Gnostic heresy was to see Yahweh, the tribal deity of the Old Testament, as a false god – a vicious and foolish creator of an imperfect world. Thus the god of the Roman Church was not the True God, but a devilish Demiurge who sought only to entrap human souls in lies, illusion, and evil.

Being trapped in the prison of this material world, the divine sparks or souls seek to transcend beyond the world ruled by the Demiurge, back home to the realm of the True God of divine wisdom whose characteristics cannot be defined or rationally understood.

For the Gnostics, one can only know the transcendent God through knowledge (gnosis) of Christ. Christ as the Son of the True God comes into the world to reveal the transcendent truth. When this concept is completely understood, one’s life assumes a new spiritual dimension, and the real virtues then begin to flow from a divine source. Christ’s message is presented equally for all comers, male and female, for as He explains in The Gospel of Thomas:

When you make the two, one, and if you make the inside like the outside, and the outside like the inside, and the upper like the lower, and so you will make the male and woman one alone, so that the female becomes male and the male becomes female, and when you make a vision in the place of an eye, and a hand in the place of a hand, and a foot in the place of a foot, and an image in the place of an image, then you will enter the kingdom.

In the end this may be the greatest secret hidden in the saga of Mary Magdalene, the woman Jesus loved.

Footnotes

1. Jean-Yves Leloup, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, Inner Traditions International, 2002.

2. James M. Robinson, Nag Hammadi Library in English, Harper SanFrancisco, 1990.

3. Jean-Yves Leloup, Ibid.

© Copyright 2005 by New Dawn Magazine. This article first appeared in New Dawn Special Issue No. 1. For further information visit www.newdawnmagazine.com